record of its development is defined, preserved and shared through the very tools that evolution itself brought about. From the oracle bones of China to the digital archives of Wikipedia, the history of writing, publishing and communication reflects thousands of years of thought, innovation and competition that provide the starting point for our company’s work, and that give perspective to our own contributions.

The pervasive influence of written

communication, and the intimate

relationship between that subject

and the tools for analyzing it, mean

The record

of written

communication

is defined and

preserved by

the very tools

that it made

possible. that the resources for further study are almost unlimited, and may be found in literally every library, every newsstand, and every museum in the world. Even as they fulfill their primary purpose of preserving and delivering content across time and distance, the means of written communication also serve in themselves as a tangible record of technological progress.

At Uhlig, we believe that the problems and goals of communication have remained essentially unchanged over the millennia, even as the tools for addressing them have continuously evolved. From the challenges of

A researcher examines an old manuscript at the United States National Archives.

The intimate relationship between technology, language and writing was reflected in the speed with which movable type was adopted in Europe after 1450 C.E. Similar technology was invented in China some four centuries earlier, but its adoption was slowed by the complexity of the Chinese writing system, among other factors.

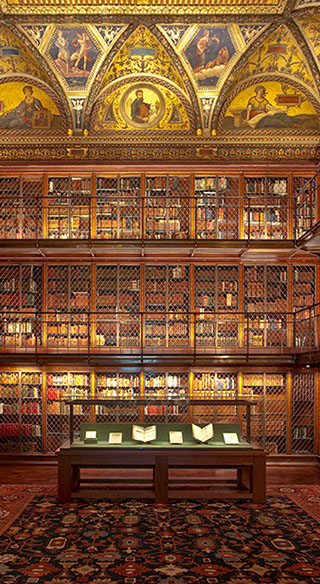

Once the private collection of

legendary financier Pierpont

Morgan, the Morgan Library &

Museum in New York (above top)

includes masterpieces of print and

manuscript illumination. The

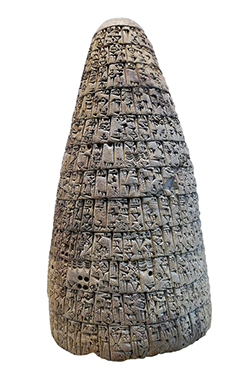

Morgan also includes one of the

world's most extensive collections

of ancient Near Eastern seals and

tablets, dating to the fifth

millennium B.C. (above).

authentication and security, to the tension between immediacy and depth, to the subsidization of high-quality content, to the protection of intellectual property, the issues we face today have shaped communication for thousands of years. The answers, too, remain just as relevant – and indeed critical – to modern life as they were to the ancient Sumerians, the medieval Catholic Church, or the tabloid press barons of late 19th-century New York City.

Understanding the lessons of the past, and integrating them with the power of technologies that are just appearing is an essential part of our company’s success. Using the wealth of knowledge that is available to us through the kinds of irreplaceable resources listed here, we believe that looking for answers is the best way to find them.

A researcher examines an old

manuscript at the United States

National Archives (above left).

The intimate relationship between

technology, language and writing

was reflected in the speed with

which movable type (bottom left)

was adopted in Europe after 1450

A.D. Similar technology was

invented in China some four

centuries earlier, but its adoption

was slowed by the complexity of

the Chinese writing system, among

other factors.

One of the most important repositories of ancient writing in the world, the British Museum’s collection of cuneiform tablets contains approximately 130,000 texts and fragments, including the royal library of Ashurbanipal, who ruled ancient Assyria from approximately 668-630 B.C. Discovered in 1850 in what is now Iraq, the Library includes historical inscriptions, letters, administrative and legal tablets, as well as divinatory, magical, medical, literary and lexical texts.

A joint project of the University of California at Los Angeles and the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin, the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative seeks to create unified web access to the historical records of the ancient Near East. Using technology to facilitate digital preservation and research, the project is working to preserve the heritage of the cradle of civilization, stretching from ancient Israel and Syria across Anatolia to Assyria, Babylon and Persia.

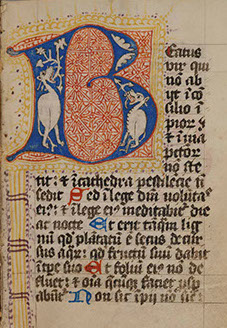

The Digital Scriptorium is an image database of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts that unites scattered resources from many institutions into an international tool for teaching and scholarly research. Digital Scriptorium is free of charge to all those who use its resources, and is supported by private gifts and a consortium of institutions ranging from the University of California, Berkeley to the New York Public Library.

Located in the birthplace of German metalsmith Johannes Gutenberg, the museum documents his invention around 1450 of movable metal type in Europe, which made possible mechanical printing and marked the beginning of the modern era of communication. Housed in a 17th-century mansion, the museum traces the development of writing and printing around the world, and includes a replica of Gutenberg’s press as well as two copies of his most famous work, the Gutenberg Bible.

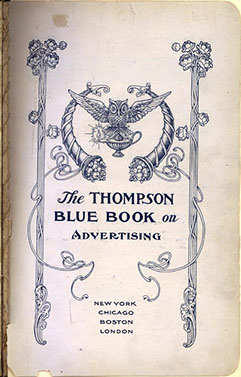

Formed in 1992 as part of the David M. Rubenstein Library at Duke University, the Hartman Center acquires and preserves printed material and collections of textual and multimedia resources and makes them available to researchers around the world. Its holdings include more than three million items that document the history of sales, advertising and marketing throughout the past two centuries.

One of the greatest repositories in the world of ancient seals and tablets, historical manuscripts, early printed books and rare cultural documents, the Morgan is housed in the former private library of financier Pierpont Morgan (1837-1913) in New York City. The library’s online database, CORSAIR, provides access to over 250,000 records for medieval and Renaissance manuscripts, cylinder seals, rare books, and other scholarly holdings.

Located on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania, the Schoenberg Institute is dedicated to bringing manuscript culture, modern technology and people together. In addition to its internal projects, the Institute supports scholarly work regarding manuscripts and manuscript culture throughout the world.

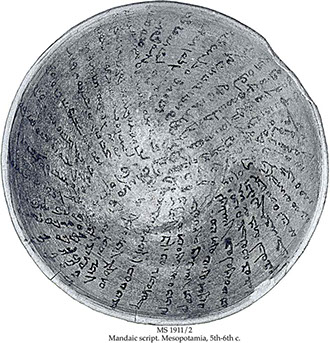

The Schøyen Collection is the largest private manuscript collection formed in the 20th century, and is composed of a wide range of materials, manuscripts and artifacts reflecting the development and cultural importance of written communication. Located in Oslo and London, the collection was started in 1920 by M.S. Schøyen, and expanded by his son, Martin Schøyen. It contains more than 13,000 manuscripts and inscribed objects spanning more than five millennia.

“There is nothing like

looking, if you want

to find something.”

— J.R.R. Tolkien